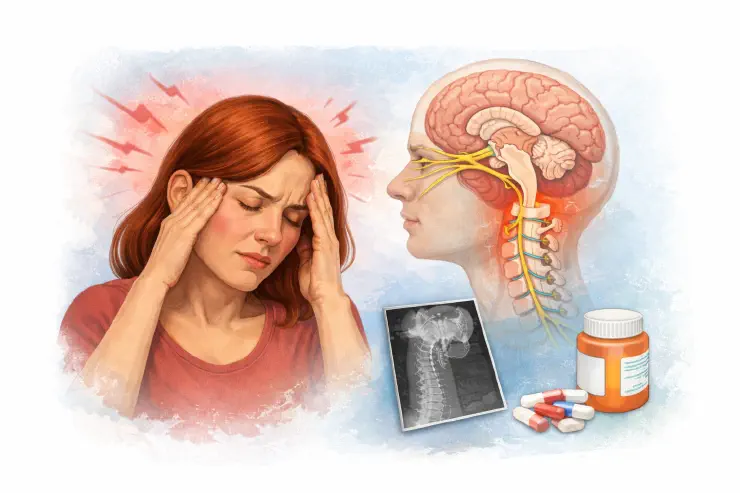

When most people visit a doctor for a headache, they expect answers. They sit in front of a medical doctor and leave with the same conclusion: “You have migraine” or “You have a tension headache” and they are given a prescription. What they rarely hear is that their pain might begin just inches lower, in the joints of the upper neck.

This blind spot is not because doctors are careless. It begins in medical education. MDs study the anatomy of the cervical spine but rarely its role in brainstem sensitization. The trigeminocervical complex where trigeminal (head) and cervical (neck) nerves converge is the missing link in most textbooks.

To many MDs the neck doesn’t enter the conversation unless there is a fracture, arthritis, or something visible on an MRI. Subtle dysfunctions are invisible in a system that values scans and prescriptions over hands-on evaluation.

By contrast, DOs (Doctors of Osteopathic Medicine) in the U.S. are taught OMT (osteopathic manipulative treatment). In theory, this makes them better equipped to recognize how dysfunction at C1 and C2 vertebrae area (upper neck) can trigger headaches through brainstem irritation. Yet in practice, many DOs stop using OMT after residency, adopting the same patterns as MDs.

Outside the U.S., however, where “DO” usually means a practitioner is trained almost entirely in manual osteopathy, this awareness is much stronger. In Europe, Canada, and Australia, osteopaths routinely assess the cervical spine in headache patients because for them, structure-function connections are central. So, the problem is not that the knowledge doesn’t exist. In the U.S. mainstream medicine this knowledge is either never taught in depth or quietly ignored.

Case Story: Anna’s headache journey

Anna was a 38-year-old attorney from Chicago who had lived with debilitating headaches for more than a decade. She had consulted multiple specialists, undergone MRI scans and laboratory testing, and tried various medications including triptans, beta-blockers, and antidepressants, yet nothing brought lasting improvement or helped her truly heal.

Gradually, Anna began to fear that something was permanently wrong with her brain. Despite numerous evaluations, not once did any clinician carefully examine the mechanical function of her neck.

When Anna came to our clinic, the approach was different. We performed a detailed postural assessment and palpated the upper cervical region. What we found was not a neurological disease, but a mechanical dysfunction at the C1–C3 levels, interfering with normal communication between the neck and the brainstem.

Through a series of precise osteopathic manual treatments, her headaches began to change. Within three months, the frequency and intensity of her attacks decreased dramatically, from daily migraines to only occasional, mild discomfort.

For Anna, this experience was transformative. She realized that her pain was not the result of a hidden brain disorder but of a correctable biomechanical imbalance that had gone unrecognized for years.